The Mt Wilhelm Adventure

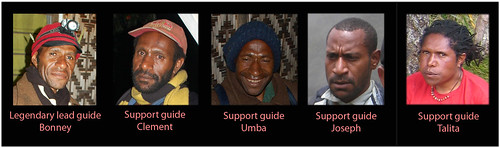

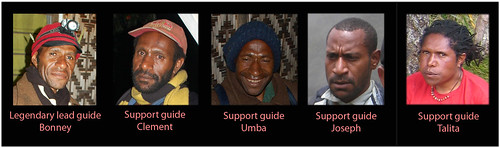

Bonney. The most legendary mountain guide in PNG

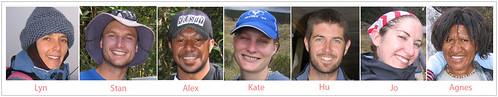

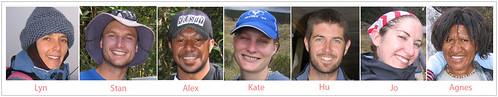

The A-Team

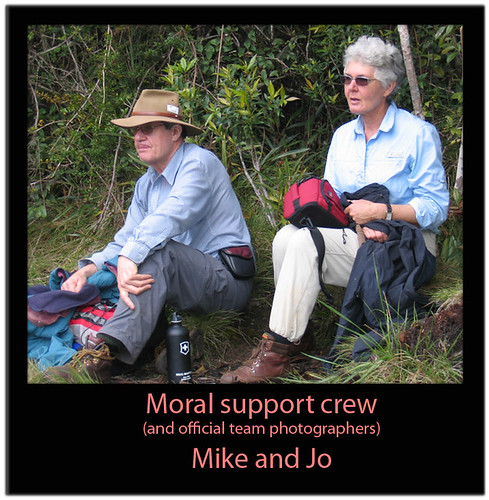

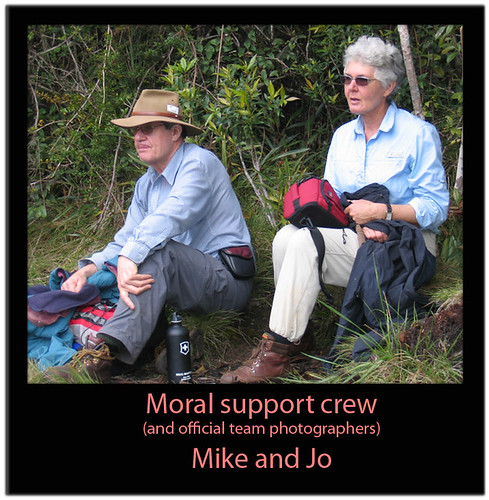

Stepping out of the A-frame and onto the tundra with bellies full of hot tea and crackers, it was a good thing we couldn’t see the looming mountain ahead. Due to the cold and anxiety about our pending adventure, most of us hadn’t slept the three hours needed for rest between dinner and the alarm sounding at 11.30pm. We’d been warned by those who had previously completed the Mt Wilhelm trek that if we wished to avoid cloudy views at the summit, we must get to the top by sunrise. And so it was that our motley crew of 12 – seven expats and five local guides – paused briefly by the lower of the Pindaunde lakes under a starry Chimbu sky at 1am to offer a prayer to God and all ancestors sundry for a safe return. This satisfied both the religious and superstitious members of the group and gave even the most cynical among us a memorable case of goosebumps. “Safe and victorious” – the parting wish of our support crew in Hu’s parents, who had left us to return to Betty’s Lodge near Kegsugl earlier that afternoon – became the motto for the trek. And although the safe return should have been the primary concern, victory was foremost in my mind as I volunteered to be the first of our group in line behind the lead guide. If I was going to be breathing hard on this mountain I certainly did not want the psychological disadvantage of bringing up the rear.

Our brilliant guides

Part one of the journey took us through relatively flat grasses, around the waterfall connecting Lake Man and Lake Meri (we women had earlier rolled our eyes in mock surprise when first told that Lake Meri ‘woman’ was the smaller and lower of the two) and up the first steep section of slope leading towards the WWII plane crash site. Of course, the wreckage was indiscernible in the dark. In fact, with no moon, there was little visibility at all – probably just the thing for getting up three quarters of a 1000m ascent. With some knees screaming after a particularly difficult first section, Bonney the boss guide called the procession to rest and drew us all in close to explain we had “just completed the first hardest part”. This was, of course, just what we needed to hear and sustained most of us until we reached and conquered “the second hardest part” – at which time we started to wonder just how many difficult parts made up this crazy hike! About halfway up the mountain we reached the saddle – a sheer grassy ridge connecting the two main sections of mountain. We were surprised to feel the sudden upsurge of wind from either side, and our head torches confirmed both the sheer drop left and right and a sudden flurry of snowfall. It was hard to believe that after snorkeling together on an island off Port Moresby just a fortnight earlier, we were now experiencing full alpine conditions!

Panorama of the Pindaunde Lakes

Inevitably, some members of the group dropped behind and the guides chose to separate the team according to speed to ensure the faster among us would have early clear views from the top. Potential separation had been factored in earlier and was part of the reason we hired so many guides. About three quarters of the way up, one member of our group noticed what seemed to be first light but was quickly corrected by a guide who explained it was the light emanating from neighbouring Madang Province’s Ramu Sugar processing plant. The Yonki hydro power station could also be seen as a section of urban-like glow in the distance.

After many hydration, rest and scroggin stops (our energy food of choice on the trek), Bonney stopped us for a quick systems check. Unbeknownst to most of us, two of our guys were not doing so well. Hu was suffering from a serious case of headaches and nausea and Alex was noticing a creeping asthmatic complaint. To his credit, Bonney didn’t even give the guys a choice. It was safety first as he turned Alex around, sending him back down to the thicker oxygen reserves. Hu was given the choice to return with Alex or stay at the current location with another guide to watch the sunrise. He chose the latter and we were later appreciative of the photos.

And so, for the final leg, Stan, Lyn, Kate, Bonney and I continued on, stopping only to photograph one of the most intense sunrises we had ever seen or to acknowledge the various memorials and makeshift graves marking the final resting places and fated sites of earlier explorers. A young Israeli who had lost his footing. An airline executive who had suffered a heart attack. A national who had made a barefoot attempt at a short-cut between Chimbu and Madang Provinces. The number of fatalities and variation in circumstance seemed to rise exponentially and unnervingly with the altitude.

Sunrise on Mt Wilhelm

The terrain quickly changed to resemble a barren Mars-scape in the last section and around every sheer ledge we expected to see the summit. But, surprisingly, it wasn’t until just 20 minutes from our destination that we saw the metal sign atop the final rocky outcrop. Looking at it, the summit seemed to have a high degree of difficulty but, in fact, wasn’t so hard to climb. We were all weary and cold by the time we touched the tin but exhilarated at having finished. Bonney told us it was the coldest ascent he had ever made in his 17 years of leading Mt Wilhelm expeditions. My frozen, swollen fingers concurred. High winds ensured obscuring cloud kept screaming across the summit, but this gave us rare glimpses of the coast. But despite the obstruction, nothing could have dampened our feelings of achievement.

Me with the legendary Bonney on the summit

Lyn enjoying the 'views'

After a series of photos, we looked down and noticed Agnes Ambele (a doctor from my hospital who had joined us on the trek) trudging up the final leg with two guides in tow. We cheered her on and were so impressed by her determination (she had turned back just an hour into the climb with a group of my friends who had attempted the trek two weeks earlier.) Unfortunately Aggie’s camera batteries had died and so our group was forced to wait just below the summit while she took my digital to the top for posterity. We drank and ate and tried to keep warm, then set off back down the mountain once Aggie had descended. At this stage, our legs were shaking in protest with the knowledge we had to do the entire trek again! But thanks to physiology and gravity, we employed entire new sets of muscle groups and tried to get back into the zone.

Again, the two groups parted – but we were no further than 20 minutes back down the mountain than we were hearing calls from behind us on the upper ridge. Ambele was in trouble. Bonney went back, sent Talita – the owner of the A-frame and Aggie’s friend and walking companion – down to us, where we gave her some altitude sickness medication, clothing and Panadeine to take back. We weren’t sure the Diamox would work but thought that even if it was an effective placebo, it might just get her down those couple of hundred crucial metres to thicker air. The guides got her moving a little and we backtracked some, meeting part way. By this stage, she was sitting on the track, eyes rolling back in her head with nausea and a headache, so we were rather concerned about her condition. We knew the best thing for her was to descend but there was no way she could possibly move. I knelt down in front of her and asked her to tell me what her symptoms were. Well the symptoms were soon all over the path in front of me. She seemed to feel a bit better after that and so what was originally an emergency plan devised by Bonney for us five to descend as quickly as possible and call for a rescue chopper, thankfully became just a request to send the couple of extra guides for assistance (the ones who had turned back for base camp earlier with those walkers who had aborted the mission).

An hour later, we had reached a sun belt and were breathing much easier. We stopped to look back but could only see the figures of the two guides in the distance. My entire body went cold as I assessed the situation. There was only one possible scenario in which two guides would leave a sick hiker on a mountain, and I started to panic at the thought of breaking the news to our hospital’s Director of Medical Services! Then, relief! Talita told us she could make out three figures! Aggie was moving. So we started off again, knowing we now had the luxury to stop for the occasional Kodak moment and to rest our weary legs.

Girls on the final descent

Back down at base, we were welcomed by our proud comrades with hot soup and noodles. Never has sun on my face and warm food in my belly felt so good. After a couple of hours rest, we begrudgingly decided to make the two hour trek back down to Betty’s Place – the lodge below base camp. None of us could imagine walking any further but the thought of smoked trout, hot tea, fresh strawberries and a warm bed was enough to set us all to our reserve auto-pilot functions. A terrific thunderstorm began ten minutes from our destination but none could be bothered fishing around in their packs for wet weather gear. We knew showers were imminent. Once more, Hu’s parents were there to photograph the weary travelers, dish out gratefully accepted sympathy and listen to our tales of adventure. Suffice to say, no one had trouble sleeping that night.

Our indefatigable support team

The A-Team

Stepping out of the A-frame and onto the tundra with bellies full of hot tea and crackers, it was a good thing we couldn’t see the looming mountain ahead. Due to the cold and anxiety about our pending adventure, most of us hadn’t slept the three hours needed for rest between dinner and the alarm sounding at 11.30pm. We’d been warned by those who had previously completed the Mt Wilhelm trek that if we wished to avoid cloudy views at the summit, we must get to the top by sunrise. And so it was that our motley crew of 12 – seven expats and five local guides – paused briefly by the lower of the Pindaunde lakes under a starry Chimbu sky at 1am to offer a prayer to God and all ancestors sundry for a safe return. This satisfied both the religious and superstitious members of the group and gave even the most cynical among us a memorable case of goosebumps. “Safe and victorious” – the parting wish of our support crew in Hu’s parents, who had left us to return to Betty’s Lodge near Kegsugl earlier that afternoon – became the motto for the trek. And although the safe return should have been the primary concern, victory was foremost in my mind as I volunteered to be the first of our group in line behind the lead guide. If I was going to be breathing hard on this mountain I certainly did not want the psychological disadvantage of bringing up the rear.

Our brilliant guides

Part one of the journey took us through relatively flat grasses, around the waterfall connecting Lake Man and Lake Meri (we women had earlier rolled our eyes in mock surprise when first told that Lake Meri ‘woman’ was the smaller and lower of the two) and up the first steep section of slope leading towards the WWII plane crash site. Of course, the wreckage was indiscernible in the dark. In fact, with no moon, there was little visibility at all – probably just the thing for getting up three quarters of a 1000m ascent. With some knees screaming after a particularly difficult first section, Bonney the boss guide called the procession to rest and drew us all in close to explain we had “just completed the first hardest part”. This was, of course, just what we needed to hear and sustained most of us until we reached and conquered “the second hardest part” – at which time we started to wonder just how many difficult parts made up this crazy hike! About halfway up the mountain we reached the saddle – a sheer grassy ridge connecting the two main sections of mountain. We were surprised to feel the sudden upsurge of wind from either side, and our head torches confirmed both the sheer drop left and right and a sudden flurry of snowfall. It was hard to believe that after snorkeling together on an island off Port Moresby just a fortnight earlier, we were now experiencing full alpine conditions!

Panorama of the Pindaunde Lakes

Inevitably, some members of the group dropped behind and the guides chose to separate the team according to speed to ensure the faster among us would have early clear views from the top. Potential separation had been factored in earlier and was part of the reason we hired so many guides. About three quarters of the way up, one member of our group noticed what seemed to be first light but was quickly corrected by a guide who explained it was the light emanating from neighbouring Madang Province’s Ramu Sugar processing plant. The Yonki hydro power station could also be seen as a section of urban-like glow in the distance.

After many hydration, rest and scroggin stops (our energy food of choice on the trek), Bonney stopped us for a quick systems check. Unbeknownst to most of us, two of our guys were not doing so well. Hu was suffering from a serious case of headaches and nausea and Alex was noticing a creeping asthmatic complaint. To his credit, Bonney didn’t even give the guys a choice. It was safety first as he turned Alex around, sending him back down to the thicker oxygen reserves. Hu was given the choice to return with Alex or stay at the current location with another guide to watch the sunrise. He chose the latter and we were later appreciative of the photos.

And so, for the final leg, Stan, Lyn, Kate, Bonney and I continued on, stopping only to photograph one of the most intense sunrises we had ever seen or to acknowledge the various memorials and makeshift graves marking the final resting places and fated sites of earlier explorers. A young Israeli who had lost his footing. An airline executive who had suffered a heart attack. A national who had made a barefoot attempt at a short-cut between Chimbu and Madang Provinces. The number of fatalities and variation in circumstance seemed to rise exponentially and unnervingly with the altitude.

Sunrise on Mt Wilhelm

The terrain quickly changed to resemble a barren Mars-scape in the last section and around every sheer ledge we expected to see the summit. But, surprisingly, it wasn’t until just 20 minutes from our destination that we saw the metal sign atop the final rocky outcrop. Looking at it, the summit seemed to have a high degree of difficulty but, in fact, wasn’t so hard to climb. We were all weary and cold by the time we touched the tin but exhilarated at having finished. Bonney told us it was the coldest ascent he had ever made in his 17 years of leading Mt Wilhelm expeditions. My frozen, swollen fingers concurred. High winds ensured obscuring cloud kept screaming across the summit, but this gave us rare glimpses of the coast. But despite the obstruction, nothing could have dampened our feelings of achievement.

Me with the legendary Bonney on the summit

Lyn enjoying the 'views'

After a series of photos, we looked down and noticed Agnes Ambele (a doctor from my hospital who had joined us on the trek) trudging up the final leg with two guides in tow. We cheered her on and were so impressed by her determination (she had turned back just an hour into the climb with a group of my friends who had attempted the trek two weeks earlier.) Unfortunately Aggie’s camera batteries had died and so our group was forced to wait just below the summit while she took my digital to the top for posterity. We drank and ate and tried to keep warm, then set off back down the mountain once Aggie had descended. At this stage, our legs were shaking in protest with the knowledge we had to do the entire trek again! But thanks to physiology and gravity, we employed entire new sets of muscle groups and tried to get back into the zone.

Again, the two groups parted – but we were no further than 20 minutes back down the mountain than we were hearing calls from behind us on the upper ridge. Ambele was in trouble. Bonney went back, sent Talita – the owner of the A-frame and Aggie’s friend and walking companion – down to us, where we gave her some altitude sickness medication, clothing and Panadeine to take back. We weren’t sure the Diamox would work but thought that even if it was an effective placebo, it might just get her down those couple of hundred crucial metres to thicker air. The guides got her moving a little and we backtracked some, meeting part way. By this stage, she was sitting on the track, eyes rolling back in her head with nausea and a headache, so we were rather concerned about her condition. We knew the best thing for her was to descend but there was no way she could possibly move. I knelt down in front of her and asked her to tell me what her symptoms were. Well the symptoms were soon all over the path in front of me. She seemed to feel a bit better after that and so what was originally an emergency plan devised by Bonney for us five to descend as quickly as possible and call for a rescue chopper, thankfully became just a request to send the couple of extra guides for assistance (the ones who had turned back for base camp earlier with those walkers who had aborted the mission).

An hour later, we had reached a sun belt and were breathing much easier. We stopped to look back but could only see the figures of the two guides in the distance. My entire body went cold as I assessed the situation. There was only one possible scenario in which two guides would leave a sick hiker on a mountain, and I started to panic at the thought of breaking the news to our hospital’s Director of Medical Services! Then, relief! Talita told us she could make out three figures! Aggie was moving. So we started off again, knowing we now had the luxury to stop for the occasional Kodak moment and to rest our weary legs.

Girls on the final descent

Back down at base, we were welcomed by our proud comrades with hot soup and noodles. Never has sun on my face and warm food in my belly felt so good. After a couple of hours rest, we begrudgingly decided to make the two hour trek back down to Betty’s Place – the lodge below base camp. None of us could imagine walking any further but the thought of smoked trout, hot tea, fresh strawberries and a warm bed was enough to set us all to our reserve auto-pilot functions. A terrific thunderstorm began ten minutes from our destination but none could be bothered fishing around in their packs for wet weather gear. We knew showers were imminent. Once more, Hu’s parents were there to photograph the weary travelers, dish out gratefully accepted sympathy and listen to our tales of adventure. Suffice to say, no one had trouble sleeping that night.

Our indefatigable support team